Twenty two years ago today, 3 November 1987 (a Tuesday), I started my first real job. As I’m now 44 that means I have been working for half my life. (This ignores the fact that I was then 22.75, give or take, so the second half will be completed when I’m 45.5, next August.)

I knew I wanted to get into publishing in some way, even though I didn’t know much about it. I knew that adverts with bold headings like “BREAK INTO PUBLISHING!” were actually aimed at getting cold calling fodder in to work on business directories, so they were to be avoided, as was anything to do with Foyles (its act has cleaned up a lot since then). I forget how I knew these things but I did. Other than that I was anyone’s and had been spraying letters to anyone who remotely looked like a publisher the length and breadth of the country.

Ultimately work found me. My mother’s cousin Jessica Kingsley had been running Jessica Kingsley Publishers for nearly a year at this stage, working from home. She had just moved into her new office in the Brunswick Centre, a concrete monstrosity between Russell and Coram’s Fields, and she was looking to expand the operation.

We Did Lunch and she explained the set-up and the vision. Jessica was the first person I knew, even among my tech-literate friends from university, to talk about desktop publishing and publishing on CD-ROM. Her imagination was way ahead of the technology (we never did publish on CD-ROM while I worked for her) but she saw it all coming. This was October 1987. She tentatively offered me employment until December, at £6000 pro rata. I joined her a week later, in early November, during which time she had somehow scraped up an extra £500 to make my starting salary £6500, and I worked for her for four years. The pay did go up.

The Brunswick Centre – or the Brunswick, as I gather it now calls itself – is a long rectangular open air shopping centre. It’s open at both ends and the long sides on either side of the main plaza are lined with shops; then above them are flats in stepped tiers like a concrete Aztec pyramid. Jessica sublet a single room in a suite of sales offices owned by Gower Publishing. It was a pretty useless location for sales offices, tucked out of the way around a corner opposite the Renoir Cinema, which showed arty foreign films that were never going to generate much drop-in trade. Fortunately a publisher doesn’t really need drop-in trade.

Drop-in trade there was, though, not quite of the kind we would have liked. The Brunswick generated an endless supply of winos and beggars. I could go back and point to the exact place where I first encountered a beggar – a woman about my age who came up to me and bluntly, wretchedly, explained that she had no money for food for XYZ reasons, could I spare some? I was shocked, horrified, and as I was coming out of a shop with my hands full of chocolate bars ready for the journey home it seemed unreasonable to turn her down. I think I gave her a pound.

After four years of working in London, though, my heart became more hardened.

One little old lady – Polish, I think, hardly any English – in one of the flats was convinced we were the management office, so would come in with her worries and complaints. Once a very elderly, confused gent wandered in because he was looking for his GP, whose surgery was elsewhere in the complex. He was suffering chest pains and couldn’t walk any further. I sat him down and ran to the doctor’s surgery, where the impenetrable wall of receptionists simply told me to call an ambulance. He survived.

Another flat was home to a sweet, white haired old gent in a slightly decayed long coat and hat, who was the first gay man I know to have clearly fancied the pants off me. It wasn’t reciprocated. He worked as a tour guide – he said, and I assume it to be true – at the Houses of Parliament. He had spied me from a distance thanks to the office’s conveniently large studio windows and never failed to get into conversation when our paths crossed on my errands (I generally did the evening run to the Post Office, last thing before closing). We even met for a lunchtime beer a couple of times, which seemed a harmless, no-commitment sort of concession. When there was a Tube strike I was invited to stay over at his place rather than fight my way in the next day through the traffic chaos. Jessica however had already told me I could work at home during the strikes which seemed a better alternative.

I was flush with enthusiasm for my new publishing career and assumed the authors I had the honour to be publishing would share that enthusiasm. A publisher has accepted your life’s work; wouldn’t you fall over yourself to work with them and polish it up into a work to be proud of?

Well, no, apparently not. Many authors tend to assume that their work is done and polished when they turn in their draft, so responding to the publisher’s queries or returning proofs isn’t that high a priority. In fact, why show any urgency in turning in the manuscript at all? How hard can publishing a book be? If the publisher says “give us your manuscript in January and we’ll publish in June,” they tend to hear the “publish in June” bit and forget the rest. Then they are indignant and bewildered when they turn in the manuscript on 31 May and learn that it won’t be out until December because the publisher, with an unaccountable urge to keep publishing books and therefore earn money to pay the staff and stay in business, has moved another book into the available slot.

In fact, the whole notion of the publisher being bound by commercial imperatives is a bit beyond many authors. They see the publisher as a slot into which you feed the manuscript and a book comes out the other end. What’s the problem?

That was what I learned about authors.

About myself, I learned that I hate confrontation (which I knew), and can be painfully shy (which I knew), and have very little memory for names or details (which I hadn’t really realised), and can give vague assurances (“your book will be in stock next week”) far too easily. The confrontation and shyness points mean that actually chasing authors, which alas is a necessary part of any editing job, is one of my least favourite activities. I’ve got better at it over the years. The names and details point meant learning to pay more attention, take notes, write stuff down. The vague assurances meant don’t make promises you can’t personally guarantee will be kept. Life is just so much easier all round if you can be organised, and straightforward, and truthful.

Jessica had spent New Year’s Eve 1986 with a bottle of champagne and her first computer, in her own words “working out how to turn it on”. The grand sum of technical knowledge within Jessica Kingsley Publishers hadn’t advanced greatly since then. Thanks to my trusty Amstrad PCW and various temp jobs I could already turn a computer on, and I didn’t need the champagne, so I found my niche in book production, as much as anyone can have a niche in a company that small. I learnt all the dodges of preparing a manuscript in a word processor (remove double spacing and spaces before carriage returns, find and replace various common errors) and setting it in DTP (Ventura, a lovely smooth DOS-based piece of software which frankly has never been bettered, even with the latest incarnation of InDesign that I now use at work). We were way ahead of our time – when I tried to move on I was held back for a long time by the fact that my experience wasn’t yet relevant in an industry that still mostly used hot metal.

We often got books sent in on PCW discs, which meant I could edit them at home. We then had to send them off to a bureau that would put them onto 5.25″ floppies (the last generation of floppies that really could flop) for our office PCs. Jessica kindly paid for me to install a second, high density floppy drive on my PCW at home.

I once got an author’s disc where he had even broken his chapters into different subsections, each one in its own file named by subtopic. So, the contents of his book appeared on screen as a list of alphabetically ordered subsections. Oh, what fun that was to sort out. One of my first professional paid pieces of writing wasn’t science fiction, it was an essay in one of the PCW consumer magazines on how best to prepare your manuscript for a publisher.

It was four highly intense years that I enjoyed hugely, while I picked up all the basic skills I use now (everything else has just been refinement) and my loathing of London grew daily. Soon after I started work there was the Kings Cross fire: the next Christmas, by which time I was commuting up from Farnborough, there was the Clapham Common crash. I was pretty certain, given the gradual and visible deterioration of all forms of public transport, that soon there would be an incident and loss of life that made those two cases look like statistical blips. I wanted to move, to anywhere but London. By the time I left for Oxford in late 1991 my starting salary had almost doubled (I know, I know, twice not very much is still quite little).

January will be the tenth anniversary of my losing my job in medical publishing, which essentially shaped the next decade more than I dreamed could be possible. Expect more reminiscences.

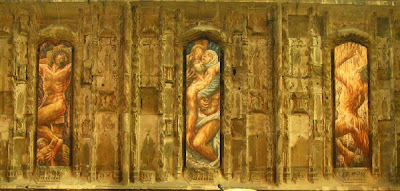

But it has a character very much of its own, especially since, as a community, it made the decision to be a sponsor of the arts and crafts. It was also being extensively renovated right up until the 1990s, still in the original style and stone; but these two facts together mean there is a lot of modern that blends very nicely with the old, and the gleaming white stonework might actually be how the entire building once looked.

But it has a character very much of its own, especially since, as a community, it made the decision to be a sponsor of the arts and crafts. It was also being extensively renovated right up until the 1990s, still in the original style and stone; but these two facts together mean there is a lot of modern that blends very nicely with the old, and the gleaming white stonework might actually be how the entire building once looked.

And there’s the more trad cathedrally stuff too. The Arundel tomb actually inspired a poem by Philip Larkin, which is actually quite good. He was moved by the way that the knight has taken off his right glove so that he can hold hands with his wife for all eternity. And it is sweet.

And there’s the more trad cathedrally stuff too. The Arundel tomb actually inspired a poem by Philip Larkin, which is actually quite good. He was moved by the way that the knight has taken off his right glove so that he can hold hands with his wife for all eternity. And it is sweet. As the local MP, this guy gets a slightly more heroic statue than his manner of death would suggest (plonker).

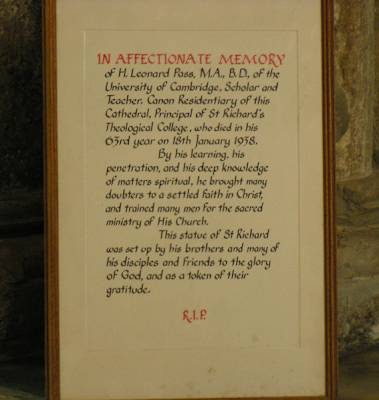

As the local MP, this guy gets a slightly more heroic statue than his manner of death would suggest (plonker). From the department of “they did it different in those days” comes this affectionate memorial.

From the department of “they did it different in those days” comes this affectionate memorial. If I had tried penetrating anyone to bring them to a settled faith in Christ then my youthwork career would probably not have lasted so long.

If I had tried penetrating anyone to bring them to a settled faith in Christ then my youthwork career would probably not have lasted so long.

… which turned out to be practice for all those times souls get lost somewhere up on a very high roof and have to be picked up. There’s probably sermon material in there if I contrive it enough.

… which turned out to be practice for all those times souls get lost somewhere up on a very high roof and have to be picked up. There’s probably sermon material in there if I contrive it enough.