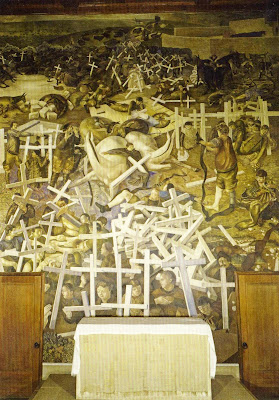

This is “The Resurrection of the Soldiers” by Stanley Spencer and it’s the first thing you see as you enter Sandham Memorial Chapel. It takes up the entire altar wall. No photography allowed so I scanned a postcard, but the real thing I could look at for hours.

This is “The Resurrection of the Soldiers” by Stanley Spencer and it’s the first thing you see as you enter Sandham Memorial Chapel. It takes up the entire altar wall. No photography allowed so I scanned a postcard, but the real thing I could look at for hours.

The walls are lined with these grotesque (in the artistic sense), blank faced paintings of Spencer’s war experiences: little emotion gets through via the faces but the body languages and the distortions make up for it. On either side the paintings lead inexorably to the Resurrection. The last painting before it on the left shows men in the trenches emerging from their foxholes at the start of another day – but even some of them are glancing over their shoulder towards it, as if aware something amazing is going on which they will get to in due course, having first got through the next 24 hours. Or not.

We’ve all seen paintings of the Last Days and all that: God’s somewhat smug elect with eyes raised adoringly to Heaven, the other lot all descending down unto gleeful demons and pitchforks. But even among the upward-bound crowd, the glorious crowd of witnesses, I’ve never had the feeling of any kind of relationship between them other than that they all made the right life choices (or possibly the right death choices).

But here we see a crowd of men who didn’t have time for thought-out choices; they lived and died together very suddenly, knocked flat by the full brutality of modern warfare, and the first thing they see on being raised up again is each other. Being British they shake hands in a rather po-faced way: “What ho, Pongo. Heard you bought it at the Somme. Jolly good show.” But judge it by the context of the times, the 1920s, and you immediately see what it’s getting at. The Resurrection isn’t just a box-ticking exercise to round off God’s plan for mankind: it’s personal and awe inspiring.

There’s probably theological significance in this chap at Christ’s feet, studying the image on the cross rather than the living original behind him. I’m wondering if he can’t quite believe it yet: he’s taken on board the theology, he knows what’s happening but can’t quite make the leap from the theory to the practical. Well, no one’s rushing him – he has all the time in … um … the world.

There’s probably theological significance in this chap at Christ’s feet, studying the image on the cross rather than the living original behind him. I’m wondering if he can’t quite believe it yet: he’s taken on board the theology, he knows what’s happening but can’t quite make the leap from the theory to the practical. Well, no one’s rushing him – he has all the time in … um … the world.

The colours are dull, the people are brutal and ugly, but I find more hope in Spencer’s Resurrection of the Soldiers than in a thousand of Michelangelo’s.

The colours are dull, the people are brutal and ugly, but I find more hope in Spencer’s Resurrection of the Soldiers than in a thousand of Michelangelo’s.