Let me add my tuppence worth – and it really is tuppence, old pence at that – to the Pratchettiana doing the rounds. Because I can.

My first short story sale was to the collection Digital Dreams, edited by David V. Barrett. My story ‘Digital cats come out tonight’ appeared alongside work by authors who included Neil Gaiman, Garry Kilworth, Storm Constantine, Diana Wynne Jones … and Terry Pratchett. This was only 1990, but even so, I knew I trod on hallowed ground.

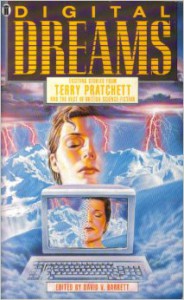

As did the publishers, who – with Terry’s permission – added a panel to the front cover announcing ‘original stories from Terry Pratchett and the best of British science fiction’. I still have an advance publicity copy of that cover, sent out by the publishers, so can attest that all the words appeared in the same font and same size, and it was down one side of the cover, while Dave’s name as editor received far more prominence.

The version that appeared in print, without any consultation with either Dave or Terry, was subtly different. Can you spot it?

The version that appeared in print, without any consultation with either Dave or Terry, was subtly different. Can you spot it?

I only caught the edges of the storm, but it wasn’t pretty: accusations flew over bigging up Terry’s name at the expense of everyone else to boost the sales (which, let’s be honest, it probably did). It was just some bright unsupervised spark in NEL’s publicity department, but it left a bad taste.

(A review in the British Science Fiction Association’s critical magazine Vector by A Well Known Author & Journalist panned it, devoting all but a few lines to the issue of the cover and finishing with a demand that Dave be expelled from the BSFA, and if no mechanism existed for doing so then one should be created. Of the stories themselves, surely the most salient part of any anthology, he said very little, which was irritating to all of us but not least to those of us hoping to break into the wonderful world of writing by this opportunity. Years later, the WKA&J approached me via a mutual friend to ask for advice on getting his son’s own novel for young people published, clearly with no recollection at all that I had any reason to recoil at his name. I pointed him at my publisher David Fickling without comment and wished the young man well. I can heap burning coals with the best of them.)

Ten years later, when I was accidentally a publisher myself, my launch title was a reprint of David Langford’s The Leaky Establishment, a wonderful send-up of his time working in the nuclear industry. (Curiously, all my big breaks in publishing have come from people called David: chronologically, Barrett, Pringle, Fickling, Langford.) When I asked this Dave if I could publish it, he dropped a mention that a big fan of the book and fellow veteran of the nuclear industry, one Terry Pratchett, had kindly offered to write an introduction if it would help get the book back in print. Was I interested?

Well, what do you think?

It’s no coincidence that Leaky was my best-selling title. And because I’m not stupid, I too wanted Terry’s name on the front cover – but I took care to ask his permission first, and to stress that I wouldn’t mistreat it as NEL had done with Digital Dreams. He replied: “Thanks. That hurt.”

Thereafter we were in the same room a few times but the only time I can say I properly met him was when I moderated a panel in Glasgow, 2005, on young adult fantasy – what is suitable to go in, what isn’t, etc. The precise title of the panel was “It’s OK, it’s Lurve: Sex in Children’s and YA Books”, which is the only explanation I can think of for how talk somehow turned to the then-current urban myth of rainbow parties. Artist Oisín McGann, also on the panel, protested that the concept was fundamentally flawed because any artist will tell you that if you just mix colours willy nilly – so to speak – you just get a bland sort of ochre.

“Well obviously,” said Mr P, “you use masking tape.”

And thus end my recollections of Terry Pratchett.