And after lunch on the day of the walk, we visited the Church of the Holy Sepulchre …

Here is the history of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in a nutshell. Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine, decided she would find the location of Christ’s crucifixion and burial, so descended on Jerusalem with all the will and force that an Emperor’s mother can command. When she demanded of the locals, “Where was Our Lord crucified?” she got blank looks in return, so starting locking people up until someone miraculously remembered.

Chronologically, of course, this is the equivalent of asking a casual passer-by in 2014 the close details of something they’ve never heard of that happened in the 1750s.

To be fair, I’m prepared to believe she found an execution site that was outside the old city walls of Jerusalem – so who knows, it could be Golgotha. Whether it was the execution site is another matter. Buried in the detritus she sound what seemed to be the remains of some crosses – including one with nail holes. The Bible says that Christ was nailed up. Ordinary perps were only strung up. Therefore this was the One True Cross, QED.

But I’m sorry to say Helena’s analytical detachment, such as it was, deserted her completely when it came to the tomb. I don’t know how many contenders there were for the site, but she found one matching the Biblical description – hewn from solid rock, only one previous owner, empty – quite literally a stone’s throw away from the crucifixion site. Christ’s tomb, QED.

That’s the bit that I really just don’t buy. Christ was buried in a tomb belonging to Joseph of Arimathea, a rich man who had had it excavated for his own eventual use. Would this powerful, respectable citizen, a member of the Sanhedrin no less, have bought his exclusive tomb plot a bare 50m from a place where lowlives were strung up to die in slow agony? Think of the people he would be seen dead with!

I think not.

But Helena did.

The rocky hill was excavated all around it so that now the tomb in its rocky shell stands on a level surface, and a succession of churches were perpetrated over both sites. The tomb is now lined with marble, hung with lamps and censers, and marvelled at by hundreds of thousands of pilgrims each year who will queue for hours for the privilege. Three or four people can shuffle in for a 30 second gawp before an impatient knock by the Orthodox priest stationed outside makes you shuffle out again for the next group, while your tour guide has a blazing argument with Russian tourists trying to jump the queue and threatens to call the police. Maybe that last bit doesn’t happen to everyone, just us.

The original “hill”, such it was, of Golgotha was left untouched. The Crusaders built a stone platform so that you can now ascend in comfort to the very top, crouch down beneath an altar erected over it and touch the very site where the cross went.

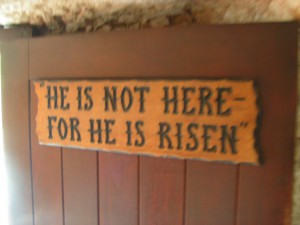

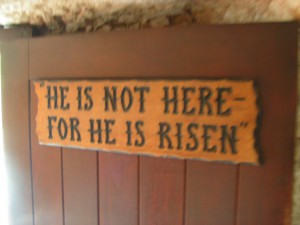

I didn’t. I honestly don’t know what happened to me in that place, but it was like a kind of spiritual anaphylaxis. I rarely feel claustrophobic but I think I did that day. Whatever the case, I found the church ugly and oppressive and as spiritual as a lump of the dead rock it is built of, with my only options to burst into tears or turn atheist. I felt the words ‘He is not here’ take on a whole new significance.

And that is why, as a symbolic equivalent of shaking the dust from my feet, I don’t intend to post any pictures of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The sponsored walk takes a break on the roof of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Yes, really. It’s a handy shortcut and surprisingly easy to do.

Well, okay, maybe just one.

So, what else did we do?

Well, Bethlehem, obviously. For some reason the Church of the Nativity didn’t upset me quite as much as its cousin over in Jerusalem. It helped that it was relatively empty, though at the right time of year I can imagine it heaving and a lot less pleasant. Also, the main body of the church is a tastefully austere Roman basilica, with what are apparently some quite gorgeous Byzantine mosaics, being restored while we were there so sadly hidden behind scaffolding.

The original Christmas decorations.

It’s only the altar end that is blingtastic, on a scale that would make Gerald Ratner re-evaluate his life. You queue up on the right hand side, then descend a few steps into the nativity grotto: site of Jesus’s birth on your right, site of the manger on the left (he wasn’t born in it, remember, just laid there). The grotto is just part of a whole network of underground caves and passages that link up with next door’s Chapel of St Jerome, though now walled off so you can’t any more get from one to the other – but come on – underground caves and grottoes FTW!

Manger, site of

Bethlehem is also worth a visit just to get it into your head how tiny and small a place it was back then; the Son of God really was slumming it by choosing it as Ground Zero for his incarnation, which is kind of the point. And once again, the geography is amazing. The original village was perched on top of a very steep hilltop. The whole area is sharp ups and downs. I always imagined “shepherds on a hillside” being far away; indeed, far too many Christmas cards show them – or someone – looking down on the town from a distance. In fact I can well imagine the hillside was right next door, because everywhere is a hillside.

Manger Square, with my back to Church of Nativity. NT era Bethlehem fitted between the two tall towers (minaret and church spire) in the distance.

Cf. David Roberts’ mid-nineteenth century painting of Bethlehem to see what I mean. All those slopes are built up now, of course.

There is of course an official Shepherds Fields site, with church and ruined monastery and … okay, we had a brief service there but I felt no sense of significance to it. Not even a holy relic sheep poo from the lamb presented to Baby Jesus, and when I think of the religious tat that was on offer, I’m astonished no one has thought of that one before.

The last full day was our Desert Experience day, attained by driving there in a comfortable air conditioned coach. Hey, we’re pilgrims, not martyrs. We stopped off in the Judean wilderness – sun baked rolling hills and plunging chasms, sheer geology in front of your very eyes. And then down to Dead Sea level (didn’t get as far as the Sea but saw it in the distance) and the plains of Jericho. The plains are essentially a rift valley between Judea and the hills of Moab t’other side of the Jordan, and the Judean hills are merely mildly warm by comparison. It helps that we were >400m below sea level, whereas when we started our sponsored walk the day before shivering in a biting wind at Jerusalem’s elevation of +700m.

The Land of Milk & Honey

When Abraham and Lot decided to go their separate ways in Genesis (like Peter Gabriel many years later), and Abraham gave Lot the choice, Lot looked upon the plains and saw that they were fertile and well watered, so chose to stay there. He must have seen them on a good day. The impression I got was more “flat and arid”, not really somewhere to manage large herds of sheep. And that would have been the first sight to greet the eyes of the Israelites when they crossed the Jordan into the Land of Milk and Honey. Gee, thanks, I bet they thought. At least in those days they would not have had to pick their way through the minefields set out to discourage incursing Jordanians.

One more river, and that’s the river of Jordan

We trod the verge of Jordan, already firmly on Canaan’s side and not an anxious fear in sight, and beheld with our own eyes the blessed site where Rupert Murdoch’s baby was baptised, 2000 years after some other guy set the trend. I dipped my hands in the Jordan to say I had and there was a chance to renew our baptismal vows. I’m not sure mine can be renewed as I never actually made any, apart from the occasional “gah” or “oo” which frankly could have meant anything. It was done on my behalf by godparents. But anyway, it was nice to be able to confirm my agreement (which I suppose I already did at my Confirmation … meh). We did not sing “Guide Me O Thou Great Redeemer”, though I felt we should have.

Then it was lunch in Jericho, sadly not pausing to look at the ruined town of that name. Modern day Jericho is built next to it – probably wisely, as I believe there’s a Biblical curse on anyone who rebuilds it.

Then back to Jerusalem, and with that, the pilgrimage was officially over. Done. Pilgrimated. But there was time for extracurricular activity and so we managed a visit to the Garden Tomb – and very glad I am too.

Garden Tomb, sans stone

This is General Gordon’s alternative tomb to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, following his fortuitous discovery of the Real Golgotha: a tomb matching all the Biblical descriptors including rollaway stone. No stone now because it, well, rolled away, but the trough before the door where it would have stood is clearly evident.

Well, maybe. Sadly I find Gordon’s logic as flawed as Helena’s, in that it’s but a stone’s throw from the alleged site. But as it’s some distance away from Helena’s Golgotha, who knows, it could be. There again there are or were doubtless hundred of rock-cut tombs.

The Garden

But, frankly, it’s not important. What is important is that the tomb is kept in a small garden, well maintained by an English charity, tranquil and relaxing, with all the noise and clamour of Jerusalem kept out by natural or manmade walls. It is an oasis of peace and calm, restoring something that I lost at the other place the day before without even realising it.

On the doorway to the Tomb: possibly not original.

And the key thing is that the tomb is empty. Even if it’s not The Tomb, it’s a visual reminder of what is important about Easter. As, I have to grant, is the one inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. I’ve been rude about that place but I can’t deny them this. Its empty tomb has helped keep the flag flying for centuries. As a clergyman on our group commented: “Just thank God that the church is full and the tomb is empty.”

Bethesda’s pools. Trust me.

On our last morning, before departing for the airport, we visited Bethesda, scene of one of Jesus’s healings and another Jerusalem site that I particularly wanted to see. The Bible gives a clear description of this place: five pools and running water. And so it was with great excitement that French archaeologists in the nineteenth century uncovered the remains of five pools in a bath complex that had (once had) running water. The five pools themselves were buried beneath a much grander bath complex put up by the Romans in honour of Aesculapius, god of healing – which to me is another good reason to believe this is the site.

The pools are next to St Anne’s church, which suggests the Crusaders who built it were astonishing acoustical engineers. It’s famous for its echoes. A soloist in an American group sang “Blessed assurance”, line by line, leaving a pause after each one, and after each one the sound persisted in the stonework for two or three seconds. Then “Amazing grace”, then “O Lord my God”. Beautiful music, but it must be a real pain for whoever reads the lesson.

Jerusalem from on high

After which, coffee and some excellent strudel at the Austrian hospice, whose roof affords a fine view over the old city, and home.

And so it was that we were able to do good to others and get a little restoration for our own souls. One week makes no one an expert, but we both feel we understand Palestine and Israel, both ancient and modern, a little bit better.

Two closing thoughts. One from our local Christian guide: “When Joshua stepped into the Jordan, the waters parted, exposing the dry land and showing the way into the Promised Land meant for the Israelites. When Christ stepped into the Jordan, the heavens parted, showing the way into the final Promised Land that is meant for all of us.”

The other from a street vendor we passed on our way back from Bethesda, offering us t-shirts, religious tat, the usual, and getting the usual polite brush off.

“No, thanks,” said we pilgrims, the memories of visiting a place where Christ transformed a man’s life still fresh in our minds and our ears still ringing with beautiful music.

“F**king tourists”, he muttered.