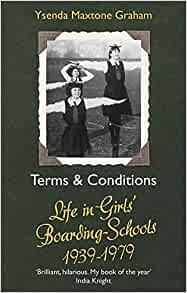

Terms & Conditions: Life in Girls’ Boarding Schools 1939-1979, by Ysenda Maxtone Graham

Terms & Conditions: Life in Girls’ Boarding Schools 1939-1979, by Ysenda Maxtone Graham

This is hilarious. The author – ex-boarding school herself – simply interviews numerous Old Girls (and some Very Old Girls), some of whom I’ve heard of (Victoria Mather, Judith Keppel, Elizabeth Butler-Sloss) and some not, about life in girls boarding schools over the given date range and sorts out the themes into a number of chapters. The dates are roughly from as far back as the oldest interviewee can remember, to the introduction of duvets, when the ambience of freezing cold dormitories and hence the traditional girls’ boarding school changed forever.

I’m all for gender equality but the fact is, girls’ boarding schools are different to boys and not just because of the gender of the pupils. There is no Enid Blyton jolly-hockey-sticks equivalent to Mallory Towers for boys. It may be because, as Graham points out, boys’ boarding schools tend to have a pedigree that starts with being founded by a monarch or at least a bishop, whereas most girls’ boarding schools seem to have been founded accidentally by a pair of nineteenth century spinstered vicar’s daughters who needed to take in a couple of pupils to make ends meet. (That might be why my school uniform was relatively comfortable while the girls up the hill wore bottle-green creations of carpeting material that were designed by computer to be exactly as unattractive as possible. A millimetre in either direction and the effect would have been ruined, but no, these ones had it nailed.) Also, there’s a certain kind of individual who is attracted to public school teaching – either gender – that definitely registers on some kind of spectrum for emotional stuntedness, and for girls’ schools in the early-mid twentieth century this effect was exacerbated by being leftovers in the buyers’ marriage market post-WW1. Too many women, not nearly enough men.

I suppose it’s because the gels were brought up to endure pretty well anything that all the ones interviewed can still laugh and shrug off the indignities, the humiliations and the fact that they were officially written off from early childhood onwards as likely to achieve anything. It’s that, or boil with futile rage. Girls’ boarding schools of the time were designed to turn out nice young women who would marry nice young men and underpin their careers until retirement. They weren’t expected to achieve anything in their own right. (The one exception is the terrifying Cheltenham Ladies’ College, which fully expected its girls to make Oxbridge, but at the cost of anything like a normal, happy, emotionally fulfilled childhood.) Paradoxically, though, I think it was because of their upbringing that so many of them were able to go on and do their own thing simply by ignoring the obstacles in their way. Some did this because the neatly ordained path of marriage, children, rich husband etc. broke down abruptly when they divorced, or the husband or the children never happened in the first place. And some did this straight off, after leaving school: one such example being the old school friend of my mother’s who gave her this book for Christmas, who had a very successful Foreign Office career and was one of the UK’s first female ambassadors. She also didn’t meet someone she was prepared to marry until her 40s.

Graham says of her interviewees that they are the best educated undereducated people she has ever met. Case in point, Madame Ambassador, with whom I had a long, pleasant chat at my parents’ anniversary party. We got on to religion and I stated my view that whichever of the world’s creeds has got closest to the truth, even that will turn out to be picture language, like using models of pingpong balls and sticks to illustrate atoms in school science labs. She gave a wry laugh and said, “our school didn’t aspire to that level of science.”