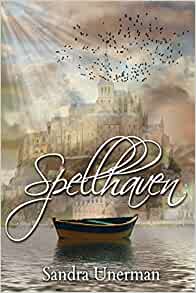

Spellhaven, by Sandra Unerman (Mirror World Publishing, 2017)

Spellhaven, by Sandra Unerman (Mirror World Publishing, 2017)

Spellhaven is a new take on the mortal-gets-abducted-by-fairies theme, in that they’re not fairies – they’re as mortal as we are – and Spellhaven is a place on earth, an island city hidden by mists and magical wards; a cross between Portmeirion and Atlantis, ruled by magician clans in an uneasy truce with the semi-feral Unseen spirits that make the place possible but also must be kept constantly placated. The Unseen love novelty, so the Magician Lords are on constant lookout in our world for anything that is new and entertaining.

Thus, in the summer of 1914, musician Jane Fairchild is judged to be sufficiently new and summoned by magical means she can’t resist to Spellhaven. The facts that it is 1914, with all the baggage of that particular date, and that we first meet Jane at a music recital, immediately set up precisely the kind of young gel that she is. Her grandchildren will probably be the early adopters of Punk but her rebellion is restricted to unconventional flute fingerings and a desire to earn her own living. Rather than an in-your-face rebel with an anachronistic in-your-face attitude, she is refreshingly and convincingly Edwardian: a rebel by the standards of her society, but still bound by social conventions of the time (very easily feeling improperly dressed without a minimum two or three layers of clothing; a cool dislike of people with country accents …).

Conflicting forces come to play once Jane is in Spellhaven. On the one hand, she has what she’s always wanted: the freedom to be musically adventurous, earning her living by what she does best. On the other there is the inconvenient truth that she has been coerced there. The people of Spellhaven are an interesting dynamic – mostly ordinary, decent types who just happen to live in a grossly unjust and unfair society. In this case the key injustice is that any outsider summoned to the city must accept a contract of service with one of the clans, or be imprisoned for twice the length of the contract they reject. Even the people whom Jane adopts as more or less allies see nothing especially wrong with this.

But this is not a story either of a spirited young woman making her escape from captivity, or settling into a bizarre form of Stockholm Syndrome. Jane does, as we would expect, start to pick up the basics of magic with the intent of using them against her captors. But then the novel takes an entirely unexpected turn halfway through, when Jane and a lot of displaced Spellhavenites suddenly find themselves back in our world. That key date of 1914 has paid dividends: it’s the middle of World War One, a fact which has gone unnoticed in the city (even though we are told the Magician Lords maintain houses and interests in cities like London and New York, which means a slight inconsistency in the tale, but not fatal). Now both Jane and her former captors are out of place. Her captors no longer have any coercive hold over her, but at the same time, Jane has nowhere to go.

Spellhaven is an intriguing novel with no easy answers or way out, which means you can keep rereading it and drawing different conclusions every time. Jane is never going to be entirely happy and settled in life – but would she ever have been, even without her magical summons?

Refreshingly, it does not appear to be part of a series: that ending ambiguity is all you’re getting and it will keep buzzing at the back of your mind for days. The book does end with a snippet of Unerman’s next, Ghosts and Exiles, a fantasy beginning in the 1930s: whether it’s a sequel of sorts, or entirely standalone, is impossible to tell, but I look forward to reading it.