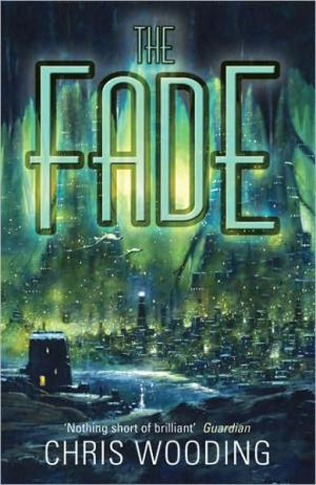

Chris Wooding – The Fade

Gollancz, 2007, 312 pp, £10.99, ISBN 978-0-575-07699-0

As well as being an exciting adventure about convincing characters in a thoroughly credible setting, The Fade is one of the most realistic novels about humans that I have read for a long time. Humanity with all its strengths and weaknesses is a basic standard that you can take anywhere; tweak a few of the basic societal parameters and you’re off. The stranger the society, the better the author has to be to make the characters within it as recognisable as the people next door. Chris Wooding is one of the better authors.

Orna is, in no particular order, a housewife, mother, assassin, ex-slave and bonded servant. She probably couldn’t articulate the difference, if asked, between the slavery of her childhood and the life debt she owes to her clan, such that she requires her chief’s consent even to have a baby and will cheat on her husband if required by a mission that the chief ordains. But she knows there is a difference. It’s the same way that to a non-believer, Catholic and Protestant both look pretty similar. These are societies that are thousands of years old and they are engrained at the most basic level of the minds of their subjects. It’s a neat trick to squeeze into 312 pages.

The world exists in the small print of Clarke’s Law, somewhere on the border between hard SF and fantasy. Probably settled by humans thousands of years ago – but there again, it was so long ago that it’s not important how they came to be there and maybe they just are – the surface is so hostile that humans had to migrate underground. It is conveniently riddled with networks of caverns massive enough to support several competing civilisations. In a harder SF novel the caverns would be far too large to support themselves and the constant rockfalls would make them uninhabitable. But this is a novel about the people and about the society. There’s magic, of a sort – or maybe it’s just arcane knowledge not shared by the general populace. We never really learn exactly what the cthonomancers do. What’s important is that they can do it.

Orna is caught up in a disastrous military operation that leaves her a widowed prisoner of war and has to escape, re-establish contact with her own side, find out what went wrong with the op and avenge accordingly. It helps to pay attention to the chapter numbers, as interspersed with all this is a series of out-of-sequence chapters describing her life from early childhood to just before the start of the tale. A lesser novel would be doing it just for effect; Wooding uses it to lay down details as the narrative proceeds that, just in time, support what comes after. I was reminded of Gromit laying down rails for his train, just before his train rolls over them. En route we encounter some truly gripping scenes, some unexpected twists, a good dose of redemption and an ending that can’t really be called happy but which certainly satisfies – and is the only ending that could have been.

I found the biggest obstacle to getting into the novel was that the present day chapters are told in the present tense, past is past, and as the novel starts in the present day it starts in the present tense. I’ve never liked this narrative style before and I had a sinking feeling that the whole novel was going to be told this way. I really enjoyed being wrong.