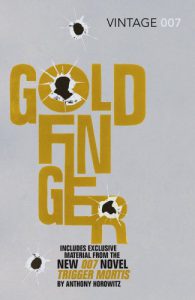

I’ve been re-reading the original James Bond novels, for the first time in about 30 years, in order of publication. Entering the Flemingverse gives an interesting glimpse of the post-war world. Austerity Britain comes off worse compared to just about everywhere else. There is still a mix of common technologies where a man who drives a 1933 4½ litre Bentley can do battle with a man intent of firing a nuclear warhead at London. It’s an exercise in culture-specific attitudes, brand snobbery, gross sexism, surprisingly less racism than I had expected, occasionally poetic insight into the ways of the world, and very wry humour. And it’s all great fun.

I’ve been re-reading the original James Bond novels, for the first time in about 30 years, in order of publication. Entering the Flemingverse gives an interesting glimpse of the post-war world. Austerity Britain comes off worse compared to just about everywhere else. There is still a mix of common technologies where a man who drives a 1933 4½ litre Bentley can do battle with a man intent of firing a nuclear warhead at London. It’s an exercise in culture-specific attitudes, brand snobbery, gross sexism, surprisingly less racism than I had expected, occasionally poetic insight into the ways of the world, and very wry humour. And it’s all great fun.

I’ve just finished Goldfinger. It was made into the third Bond movie, so it comes from that time when the movies stuck reasonably close to the original plot. This is the seventh novel in the series, but for some reason it’s the one where I was particularly struck by the similarities and differences between novel and movie: what stayed the same; what changed; and which (allowing for the fact that two different art forms will always have differences) is better.

The book is by no means perfect. For example, I’ve never understood the allure of Pussy Galore. She comes in on page 167 of a 224 page novel, and is a lot more interested in Tilly Masterson (still alive at this stage in the book; in the movie she is killed off about five minutes after appearing) than in Bond. She is happy to go along with Goldfinger’s plan, until she decides on page 216 to switch sides, with no discernible impact on the plot at all other than giving Bond someone to have sex with shortly after the last page. The interaction between her and Tilly is cringeworthy and you have to wonder if Fleming had actually met any lesbians. (I suspect the answer is: in fact, yes; knowingly, no. Note also: “She said, not in a gangster’s voice, or a Lesbian’s, but in a girl’s voice, “Will you write to me in Sing Sing?”” In the Flemingverse, gangsters, lesbians and girls all have distinctive voices. It’s fun to imagine Honor Blackman saying novel-Pussy’s lines.)

However in the Flemingverse a lesbian is only a woman who hasn’t met the right man yet and on the last page she sure enough melts into the right man’s arms.

Half the denouement is in flashback, thus giving it the excitement of a strand of wet spaghetti. Bond, Goldfinger at al are on a plane, as per the movie. It’s Oddjob who gets sucked out of the window. Goldfinger just gets throttled. The plane doesn’t have fuel to reach land, so Bond holds the crew at gunpoint and orders them to ditch the plane in the sea near to a weathership. And that is the bit in flashback – one moment the plane hits the water, the next Bond and Pussy are safe on board the ship, remembering how the plane snapped in two upon impact and took the crew and its cargo of gold to the bottom of the sea. The final special effect of the novel, so to speak, relegated to memory. Come on! The movie probably couldn’t have managed it within the budget, but the effects budget of the imagination is unlimited. I just have the feeling Fleming got bored at that point and wandered off.

But on the plus side …

The novel opens with Bond having a one-corpse-too-many angst attack, having just had to exercise his double-0 licence yet again. It’s a flash of vulnerable humanity that none of the screen Bonds have been allowed to show. The plot continues, recognisably similar to the film, though Jill Masterson’s death by gold paint occurs off stage. The golf match between Bond and Goldfinger is just as tense and just as funny, but Bond is invited to a post-match dinner with Goldfinger, and only just avoids giving himself away as a spy by setting up Goldfinger’s cat as the guilty party who has interfered with all the hidden internal cameras in Goldfinger’s home. Goldfinger gives the cat to Oddjob for dinner, raising the utter bastard score to 15-all.

Bond sets off across Europe after Goldfinger, in a chase that is much more exciting on paper than on screen. On screen, Bond simply uses a beep machine overlaid on a map. On paper, he has to use his own judgement as to Goldfinger’s route, based on only on the strength of the homing signal, and gets it wrong on a couple of occasions, requiring quick thought and fancy driving to rectify. His journey across Europe is lovingly described – the landscapes, the weather, the food and wine sampled en route – and again the grey 50s Britain that the readers knew comes off much worse by comparison. Then Tilly Masterson enters the story and royally screws Bond’s plans up, and both are captured. This is the “no, Mr Bond, I expect you to die” scene from the film. But this is where the really interesting difference sets in. Goldfinger spares both Bond and Tilly because he suddenly realises he has need of them.

The set piece, Goldfinger’s magnum opus, is to knock off Fort Knox. Between the book and the movie, someone worked out that shifting Fort Knox’s gold reserves would be impossible in the time allowed, so the movie plot was changed to make Goldfinger want to irradiate America’s gold supply and ruin its economy. Either version is a major logistical challenge which means that Goldfinger has to recruit several different American crime syndicates for their resources and coordinate a very large operation. In the movie, he tells the crime bosses about his plans, kills the one who won’t play ball, and then kills the others anyway – I never did understand that. In the book he fully intends to recompense them for their work, in gold, so they all survive apart from the one dissenter. And he decides at the last minute – as a whizzing circular saw draws ever closer to Bond’s whizzing apparatus – that he needs Bond and Tilly as respectively an administrator and a secretary to make the whole complex operation run smoothly.

You have to wonder why this didn’t occur to him at any point in the planning stages. Maybe he’s just not a details man. Anyway, this is the first and I think only time that a Bond villain acknowledges the administrative and logistical overhead of running a major villainous operation. It appeals to me as a writer and as a science fiction fan, wanting to know how things work and make the fictitious world internally coherent. Of course, the movie would have ground to a halt if it had tried to include this point, but in the novel it just ups the tension as Bond is drawn in, becoming an unwilling part of the machine he is trying to destroy. To stay alive, he has to do his job, which means make it work, because Goldfinger will kill him in an instant if he starts to slack off.

One more example of why Books Are Better.